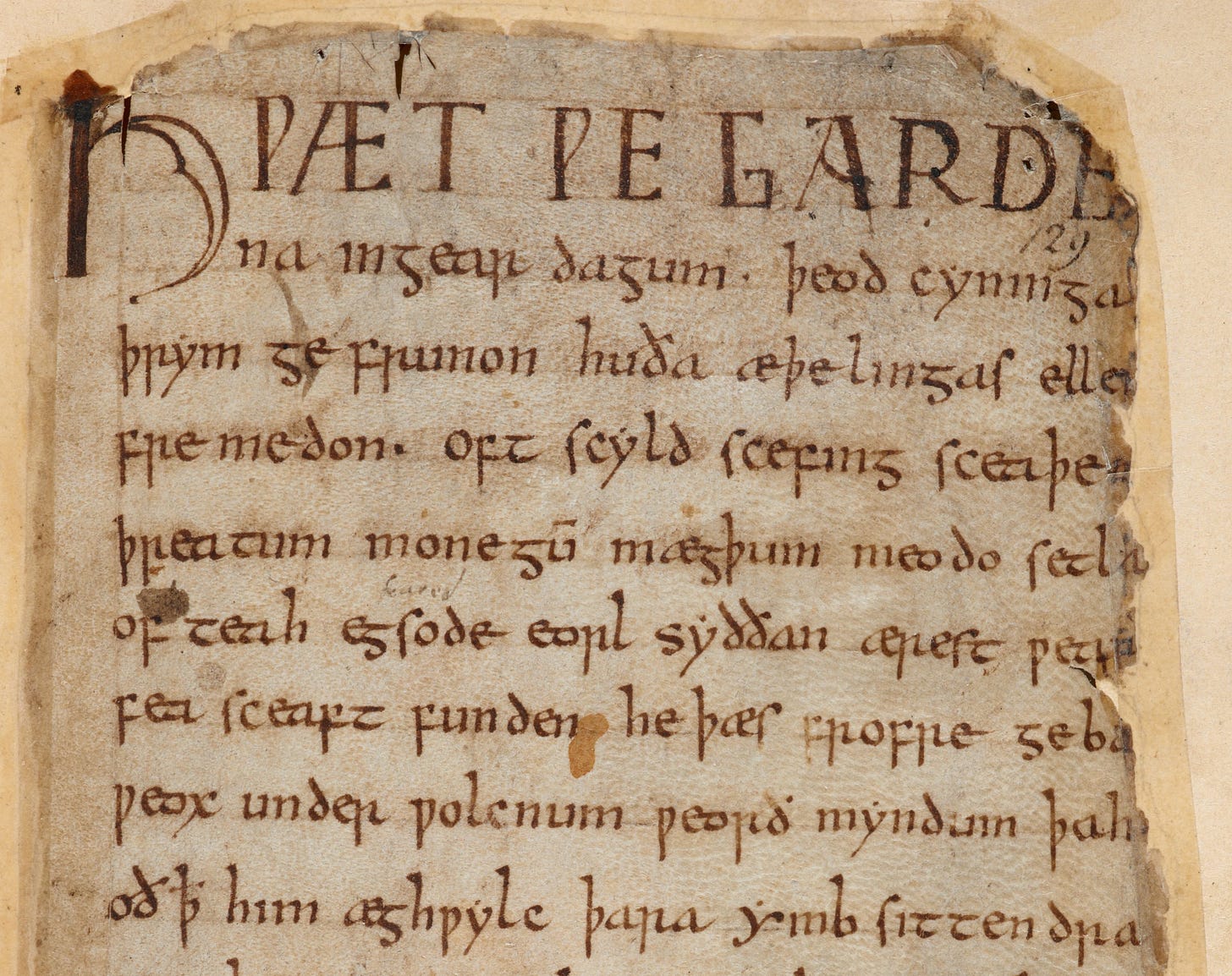

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem written sometime around the 10th century. It is the oldest and most well known piece of Old English literature. While there is some debate as to whether it originated as an oral tale or is the work of a single author—we can safetly assume that the poem is at least strongly inspired by local folklore. The story is of a warrior named Beowulf who hears word of a monster named Grendel attacking the great hall of Hrothgar, King of the Danes so he sails to Denmark from Sweden with his men and kills Grendel. As they are celebrating the next night, Grendel’s mother attacks the hall and Beowulf infiltrates her lair and kills her the next day. After being rewarded, he returns to his home where he becomes King of the Geats. One day, his kingdom is attacked by a dragon—whom he slays with the help of his thanes. Unfortunately, Beowulf soon succombs to his injuries and is buried in a barrow overlooking the sea as an honored hero.

If that doesn’t sound like part of a D&D campaign, then I don’t know what does. The fact is that Beowulf is to thank for many of the tropes and themes we often play with in heroic fantasy RPGs like D&D or Pathfinder.

There are several monsters mentioned offhand in Beowulf that can be found in your standard D&D monster manual such as giants, ogres, and ghosts. But three monsters take the main stage, Grendel, his mother, and the dragon.

Grendel is the first and, arguably, the most significant monster in the poem. He is not described as any particular type of monster, only that he is one of many monsterous decendants of Cain and was a purely evil creature. He isn’t given much of a physical description but he seems similar to a troll, giant, or gnoll. It is possible that Grendel served as inspiration for the mondern depictions of each of these monsters.

Grendel’s mother is fought immedieately afterwards in a nearby body of water. She is similarly lacking a physical description aside from having large claws like Grendel. She does fit a “mother of monsters” architype that is common in mythology like the Norse giantess Angrboda or the greek Echidna. Were I running Beowulf as a D&D campaign (really not a bad idea), I would make her an Annis Hag: a swamp-dwelling hag that controlled lesser monsters. Additionally, the concept of delving into a monsters lair is classic to the Dungeons part of D&D. Complete with fighting off smaller pesky monsters on the way to the main boss—who has the advantage of fighting in her own lair.

Lastly, the dragon hardly needs an explaination for its connection to Dungeons and Dragons. But it is worth emphasizing that this is the very first source of the modern concept of a flying, firebreathing dragon. Dragons appear in cultures all over the world as are theorized to be so common in folklore because they combine the traits of some of our worst fears: snakes, birds of prey, and large cats. The Smaug-style dragons that we see in D&D and other works of fantasy likely evolved from the Proto-Indo-European predecessor to the story of Thor slaying Jormungandr the world serpant—variations of which appeared all across europe.

Aside from monsters. Beowulf also gives us the architipal fighter hero that we see across fantasy from Aragorn to John Snow. Odds are, if you’ve played fantasy RPGs, at least one player character fits the archetype of a hero on a quest for fame, glory, and gold (and probably has some claim to the throne). This hero is also part of an adventuring party—Beowulf sails to Denmark with a crew of fellow adventurers and relies on them later to defeat the dragon. What is Aragorn without Gimli and Legolas? Finally, Beowulf is saturated in the theme of revenge. Beowulf hunts Grendel’s mother for revenge against killing Æschere, the king’s advisor. Yet, Grendel’s mother only attacked because she is seeking revenge for the death of her son. Revenge stories are extremely common in fantasy and fantasy RPGs. Odds are that half of your D&D pary’s backstories are revenge-related.

Up until now, I have already referenced J.R.R. Tolkien’s work several times. It is no surprise that it is so easy to pull from Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit because they were both strongly inspired by Beowulf. Smaug is inarguably a direct callback to the dragon of Beowulf, even down to the treasure hoard and a single missing piece being what sends him on a destructive rampage. You could spend all day talking about the connections between these works, like the similarities between Gollum and Grendel, Beowulf and Aragorn, the themes of christianity and paganism, and the general basis in Anglo-Saxon culture. But the most interesting connection to me, as well as one of the biggest tropes that D&D settings have, is the “impression of depth” or abundunce of background information that give the story the impression of existing in a complex world with a deep history—in other words, Beowulf began the tradition of worldbuilding. The poem contains tons of information that is not related to the story such as mentioning that the sword Beowulf found to kill Grendel’s mother was a sword made for giants or mentions of other kingdoms like the Frisians and the Franks warring with each other. These details exist for the purpose of making the world feel real and lived-in. Anyone who has read any Tolkien knows just how complex and fleshed out the world of Middle-Earth is thanks to these types of info snippets.

The reason Beowulf’s influence on Tolkien is so important is because Tolkien is probably the single most influential inspiration for Fantasy RPGs. The original four races of D&D are directly taken from Tolkien and the reason we see so much of Beowulf in D&D is because Tolkien carried on many of the story’s traditions and made them popular.

At the end of the day, even though Gary Gygax never mentioned Beowulf as an inspiration for D&D like he did Lord of the Rings, we should still credit Beowulf as being the original source of so many tropes that make fantasy RPG what it is. So, next time you fight a fire-breathing dragon for its hoard of gold or bore your players with a long exposition dump, take a moment to appreciate the pair of 10th century monks who transcribed Beowulf—and give it a read if you haven’t already.